PRESS RELEASE

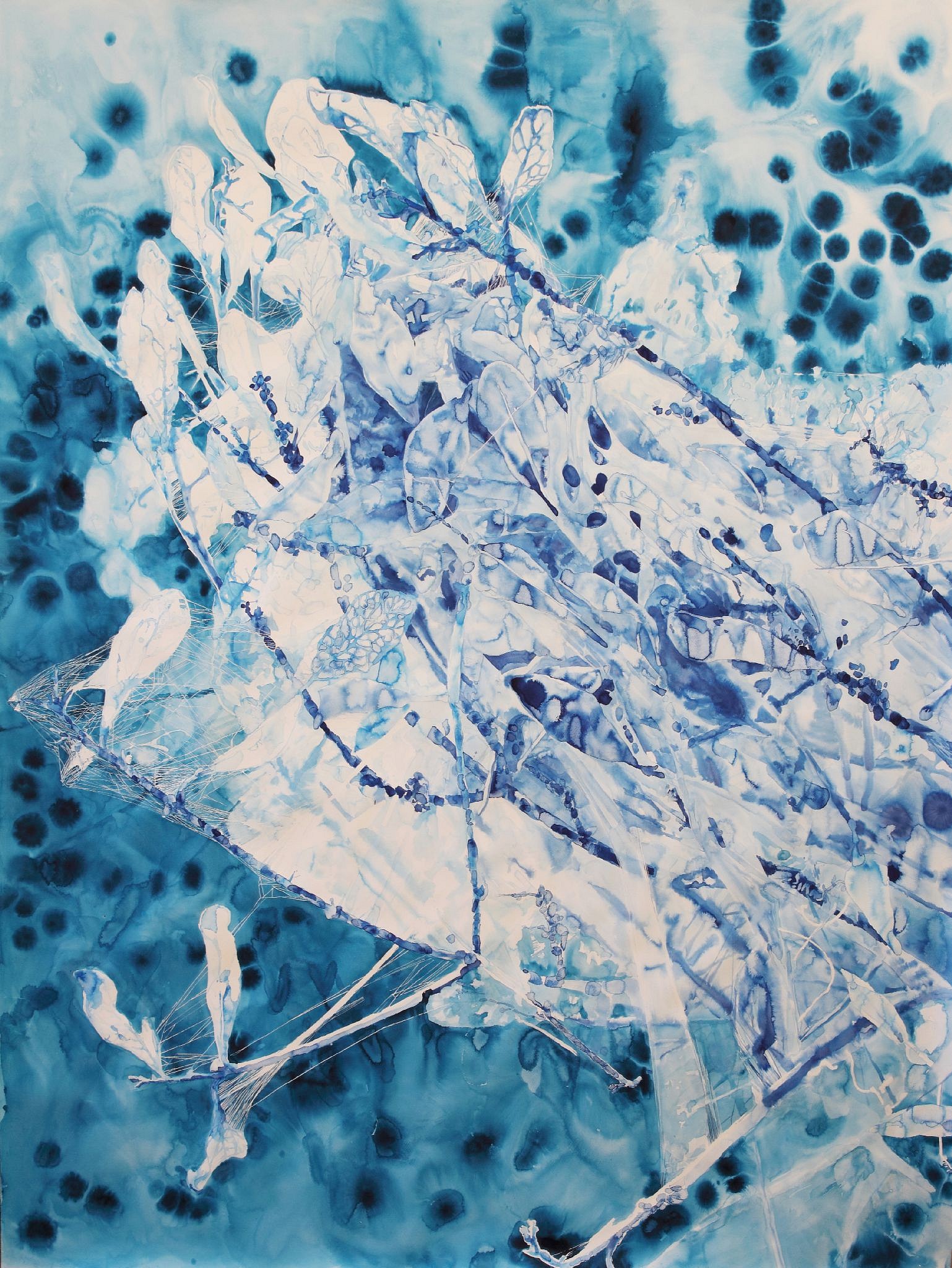

TANYA POOLE: Ancient Codes

Sep 5 – Sep 25, 2019

Everard Read CIRCA Cape Town is pleased to present Ancient Codes – a solo exhibition of new works by Makhanda based artist, Tanya Poole. Opening on the 5th of September, the exhibition runs until 25th September.

...thumping breathing organs

Fingerprint all my genes awake, Ancient codes in each and every cell...

Nomzi Kumalo, A Human Encounter, 2014

The act of art-making weaves together reason and instinct as it draws from rational consideration and instinctive urge. At points in this process, the relationship between the brain, the eye, the hand and the paper in the making of a painting feels as though it balances in a space between thought and impulse. For a Cape Weaver bird, the act of interlacing pliant green leaves of grass into a nest which strengthens as it dries is not only an outcome of innate behaviour, it is also the outcome of learnt behaviour and experience, which is why the nests of mature Cape Weavers are much better constructed and are less often destroyed by their mates.

Trees, branches, leaves, their interstices and the aspect of looking upward through these arboreal frameworks to the sky characterises the imagery in a body of work titled At the Edge of the Forest, one chapter of three in my solo exhibition The Whispering Spring. These trees I had seen almost daily in my walks through Rhodes University's Botanical Gardens and the paintings were installed in a visual and conceptual conversation with portraits of the (women) scientists and researchers who work at the Albany Natural History Museum, and 160 individual paintings of female worker bees that make up The Swarm - the collective title for these paintings of bees.

Following The Whispering Spring's opening at Galerie M, Bochum in Germany, my husband and daughter and I went to my family's house in rural France in winter, walking every day and gazing up through the winter trees, with their essential framework stripped of leaves and pared back to their characteristic and specific shapes. I contemplated the DNA that makes a poplar tree grow like a poplar and a willow a willow, thinking of the DNA my parents gave me that made me grow like me and the DNA my daughter inherited from me, that with my husband's DNA made her grow like her. I considered the chemicals in trees that let them know when to drop their leaves and when to produce buds and that are transmitted underground to other trees through what is colloquially known as the Wood Wide Web and is formally called the Mycorrhizal Network. It is a network which is not dissimilar to our own brains' network of neurons. I considered the fact of parent trees being able to protect their offspring trees and send them nutrients, water and defense signals and thought of the ancient genetic codes that form us and our offshoots. Instinctively, I continued to paint trees.

We returned to France again in spring because I missed my parents and sister and extended family. I felt a deep instinctive yearning for them and in this time, we decided to move to France from South Africa to be with them. My Dad and I would walk through the trees, we spoke about his lack of knowledge of his biological father and I discovered he had been born with a totally different name. I wondered who his father was, who his half-sisters and -brothers might be, who I was, what had I given my daughter genetically? My genealogical search continues on Ancestry.com, but subliminally I was becoming fascinated by nests: Birds' nests, insects' nests and vespiaries; fieldside grass that my young niece flattened into an instant bed; arachnids' webs, river creatures' nests on walks along the river that flows past my family's house and aquatic insects' cases that I'd photographed on field trips with my entomologist best friend; houses of creatures that shape and bend elements of their environment to create havens and nurseries. Networks of neurons, connections and blood-ties. Empty nests and family trees.

In the studio, the paintings of trees were evolving into maps and networks, matrices where things could lodge, and into ganglia, clumps and nests. I painted small nests on small pieces of paper and threw them away. They were inklings. I painted outsize nests on large sheets of paper and these felt better: in proportion to a human body, they could be a place an artist or a viewer might want to crawl inside. Colour eluded me. A few times, local colour worked - a brown weaver's nest felt right. A few other times I just kept emptying the bin. Other colour started to nudge me to shift away from description and move into a poetic register, where the semi-abstraction of the paintings could better convey the idea of nests than observational studies could, though both satisfied a gut feeling for me. The thoughts that hovered around the idea in my mind, loose and shifting, guided the marks that collected into clusters on the paper and to dovetail with the process, I kept pushing the inherent qualities of ink and water in a process which is semi-uncontrollable.

These paintings are prompted by visual hooks in the natural environment around my family's house and mine and by deep instincts around family and partnerships. They are also embellished by thoughts around the ancient codes of genetics and biology, both ours and our environment's. The process of making a painting, the thought of it and the planning of it, the mental and emotional references, the decisions on materials and scale, the construction of it, mark by mark that is like nest making, is to satisfy the urge to construct and the thought of making, to fantasise and to rationalise and this process shimmers like a web attached somewhere between instinct and reason.

Tanya Poole 2019

For the full poem A Human Encounter by the singer Nomzi Kumalo, follow the link:

https://nomzikumalo.wordpress.com/2016/02/22/